| Go-To Guide: |

|

Publication and Path Forward

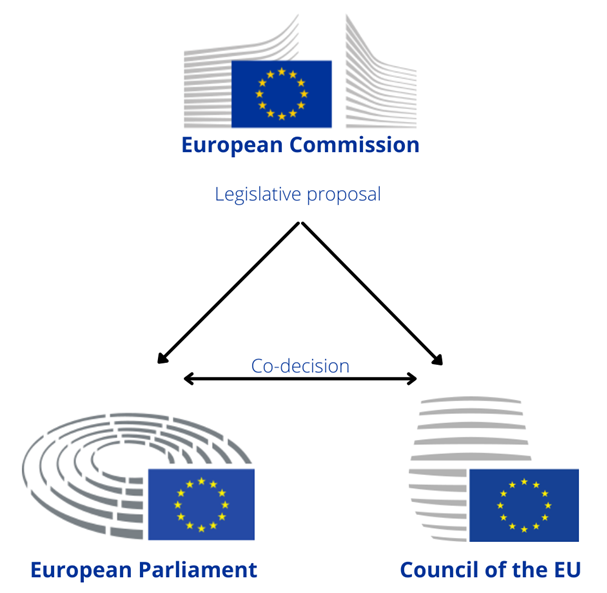

The EU Space Act is a “proposal for regulation” put forward by the European Commission. The Commission is the EU body that holds legislative initiative, or the power to make proposals for legislation.[1]

The Commission presented the draft Act to the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, the two co-legislative bodies of the EU. The presentation, and potential subsequent action of the Council and Parliament, is pursuant to Article 294 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which sets out the ordinary legislative procedure of the EU.[2]

Under Article 294 TFEU, the Parliament and Council may debate, revise, and adopt the Act. The European Parliament performs the first review of the Commission’s proposal and adopts a position, with no set deadline. The Parliament then sends its position to the Council.

Should the Council endorse the Parliament’s position, the Act becomes law as written. Conversely, if the Council does not approve the Parliament’s position, it may adopt its own position, stating the reasons therefor, and return this to the Parliament.

Upon receiving the Council’s position, the Parliament has three months to determine its course of action. It may (i) approve the Council’s position or refrain from acting, in which case the Act becomes law; (ii) reject the Council’s position by a majority vote, in which case the Act shall be considered not adopted; or (iii) propose amendments, initiating the second “reading,” or round of review.

|

HISTORIC EXAMPLE: CREATION OF THE EU SPACE PROGRAMME AND AGENCY This same procedure – presentation of a Commission proposal to the Council and Parliament for consideration and potential adoption – led to the creation of the EU Space Programme and EU Agency for the Space Programme. The Commission presented their proposal in June of 2018,[3] and by December 2020, the co-legislators reached provisional political agreement on the text. A final regulation was agreed upon in April 2021 and entered into force.[4] |

Authority to Promulgate the Act

The draft Act cites Article 114 TFEU as the legal authority for the EU to adopt a supranational space regulation.

Article 114 empowers the EU Parliament and Council to adopt measures to ensure the establishment and functioning of the “internal market.”[5] Precedent indicates Article 114 may only serve as a basis for supranational legislation when: (1) there is a finding of disparities between national rules, and (2) the differences are such as to obstruct, or be likely to obstruct, the fundamental freedoms and thereby have a direct effect on the establishment and functioning of the internal market.

The draft Act claims these two factors – disparities between national rules, and a likelihood for these disparities to affect the internal market – are present and justify invocation of Article 114 TFEU to adopt a supranational space regulation. Specifically, 13 of the 27[6] EU member states currently have national space laws,[7] and another five are planning to develop a national space law.[8] The Act claims this variation sets up a market disparity that may disrupt the internal market and which Article 114 is intended to address.

Notably, the Act presumes that authority per the TFEU under Article 114 is sufficient to overcome the exclusion in Article 189. Article 189 grants member states exclusive competence in laws and regulations related to outer space, and explicitly excludes Union authority for “any harmonization of the laws and regulations of the Member States.”[9] However, as the Act notes, “in accordance with established case-law,” Article 114 may be used as a legal basis for “establishment and functioning of the internal market” in space services.[10]

Compliance with the Principle of Proportionality

Review of the draft Act indicates the proposed scope may be open to challenge insofar as it violates the principle of proportionality.

The principle of proportionality is one of the foundational principles of EU law, enshrined in Article 5(4) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU).[11] Proportionality requires that any measure the EU adopts must be suitable to achieve the intended objective (suitability), must not go beyond what is necessary to attain that objective (necessity), and must strike a fair balance between the means employed and the aim sought (proportionality stricto sensu or proportionality in the narrow sense).

Proportionality, together with subsidiarity, acts as a constitutional check on the exercise of the Union’s competences. It applies to all actions EU institutions undertake, in particular in the context of legislative and regulatory measures. It is both a standard of institutional restraint and as a key criterion for the judicial review of EU acts, and operates as a safeguard to ensure that EU intervention remains within appropriate bounds relative to the pursued policy objectives. According to this provision, the content and form of Union action shall not exceed what is necessary to achieve Treaties’ objectives.

Necessity

It is arguable that certain provisions of the draft Act may violate the principle of proportionality because they exceed what is “necessary” to harmonize the safety, resilience, and environmental sustainability of space services. For example, the Act states the Commission “shall” develop a Union Space Label Framework “to promote enhanced voluntary adherence to high standards of protection of space activities.”[12] But no member states currently require such labels, so there is no disparity in national rules. Moreover, the draft Act recognizes methods for evaluating the environmental impacts of space activities “are clearly underdeveloped today,”[13] so it’s unclear what evidence – other than conjecture – may be offered to assert environmental labeling regimes are “necessary” for environmental sustainability.

Narrow Proportionality

The draft Act may violate proportionality in the narrow sense because there may not be a fair balance between the means, or requirements and costs, and the benefits, or aim sought.

The draft Act’s impact assessment concludes the regulations strike a fair balance because the higher costs driven by requirements of the Act would be “completely” offset by the annual benefits.[14] However, this tradeoff (costs offset by benefits) relies on the following: “The main assumption taken to carry the cost-benefit analysis was that the legislative act would reduce the amount of debris by 50% by 2034 due to increased sustainability of space activities.”[15]

This assumption is significant. It is not that the Act would slow the rate of growth of debris populations; it is that the Act would facilitate elimination of half the current debris catalogue (i.e., amount of debris) in 10 years.[16]

If the main assumption underlying the Act’s cost-benefit analysis is unrealistic, then the cost-benefit analysis is flawed. More specifically, if the Act cannot prompt a 50% reduction in the total orbital debris population in 10 years,[17] then the annual benefits would be less than claimed and may no longer “completely” offset the Act’s costs.

Conclusion

The release of the draft Act is the first step in what may be a long process of debate and reconciliation towards potential adoption. The Parliament and Council’s discussion and reconciliation of the draft Act may reduce the Act’s scope.[18] Nonetheless, operators – Union-based and international alike – should follow the Act’s evolution to remain aware of potential new laws that would impact operations globally.

[1] The European Commission is made up of 27 commissioners, including the president, with one commissioner from each EU member state.

[2] Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union art. 294, Oct. 16, 2012, 2012 O.J. (C 326) 47 [hereinafter TFEU].

[3]Commission Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing the Space Programme of the Union and the European Union Agency for the Space Programme […], COM (2018) 447 final (June 6, 2018).

[4] Regulation 2021/696, of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 April 2021 establishing the Union Space Programme and the European Union Agency for the Space Programme […], 2021 O.J. (L 170) 69.

[5] TFEU art. 114(1).

[6] The EU member states are: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden.

[7] These 13 member states are: Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Sweden.

[8] Estonia, Germany, Poland, Romania, and Spain.

[9] TFEU art. 189(2).

[10] EU Space Act, supra, at Explanatory Memorandum.

[11] Consolidated versions of the Treaty on European Union art. 5(4), Oct. 26, 2012 O.J. (C 326) [hereinafter TEU].

[12] EU Space Act, art. 111(1).

[13] EU Space Act, Explanatory Memorandum.

[14]Commission Staff Working Document Impact Assessment Report Accompanying the document Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Safety, Resilience and Sustainability of Space Activities in the Union, at 50, SWD (2025) 355 final (“Assuming that a legislative act for safe, resilient and environmentally sustainable space activities would allow for a 50% reduction of space debris over the next 10 years, the initiative would benefit satellite operators, enabling an annual benefit of EUR 677.5 million, completely offsetting the costs driven by the higher requirements stemming from the law.”) [hereinafter Impact Assessment].

[15] Id. at 49.

[16] At current levels, a 50% reduction in space debris by 2034 would require the removal of roughly 21,000 trackable debris objects. It would also include a 50% reduction in non-trackable space objects, and the introduction of no new debris.

[17] While not explicit, the impact assessment must evaluate a reduction in the total amount of existing debris in orbit, not merely a decrease in the rate at which new debris is generated. This is evidenced by the discussion of costs associated with collision avoidance. Currently, European operators in low-Earth orbit carry out approximately 1,000 collision avoidance maneuvers each year for all operational satellites (with 779 maneuvers reported in 2023). Id. at 55. The impact assessment goes on to assume that a significant reduction in space debris would correspondingly result in a 50% reduction in the number of required collision avoidance maneuvers per year. Id. at 56 (Table 19, showing projected annual maneuvers reduced to 516 for active LEO European satellites). However, this projected benefit—a reduction in collision avoidance maneuvers to half their current level— could only be achieved if the total amount of debris currently catalogued is drastically reduced. It is not sufficient to simply slow the creation of new debris; the justification for the Act presumes there must be an actual reduction in the present population of debris objects already tracked in orbit.

[18]See, e.g., Directorate-General for Comm., Simplification Measures to Save EU Businesses € 400 Million Annually, European Comm., May 21, 2025, (noting a Commission initiative to reduce “unnecessary bureaucracy and create a regulatory environment that drives” innovation and growth, and which includes proposed simplification of provisions of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)).